Name: Katrina Dank, MS2, Seattle

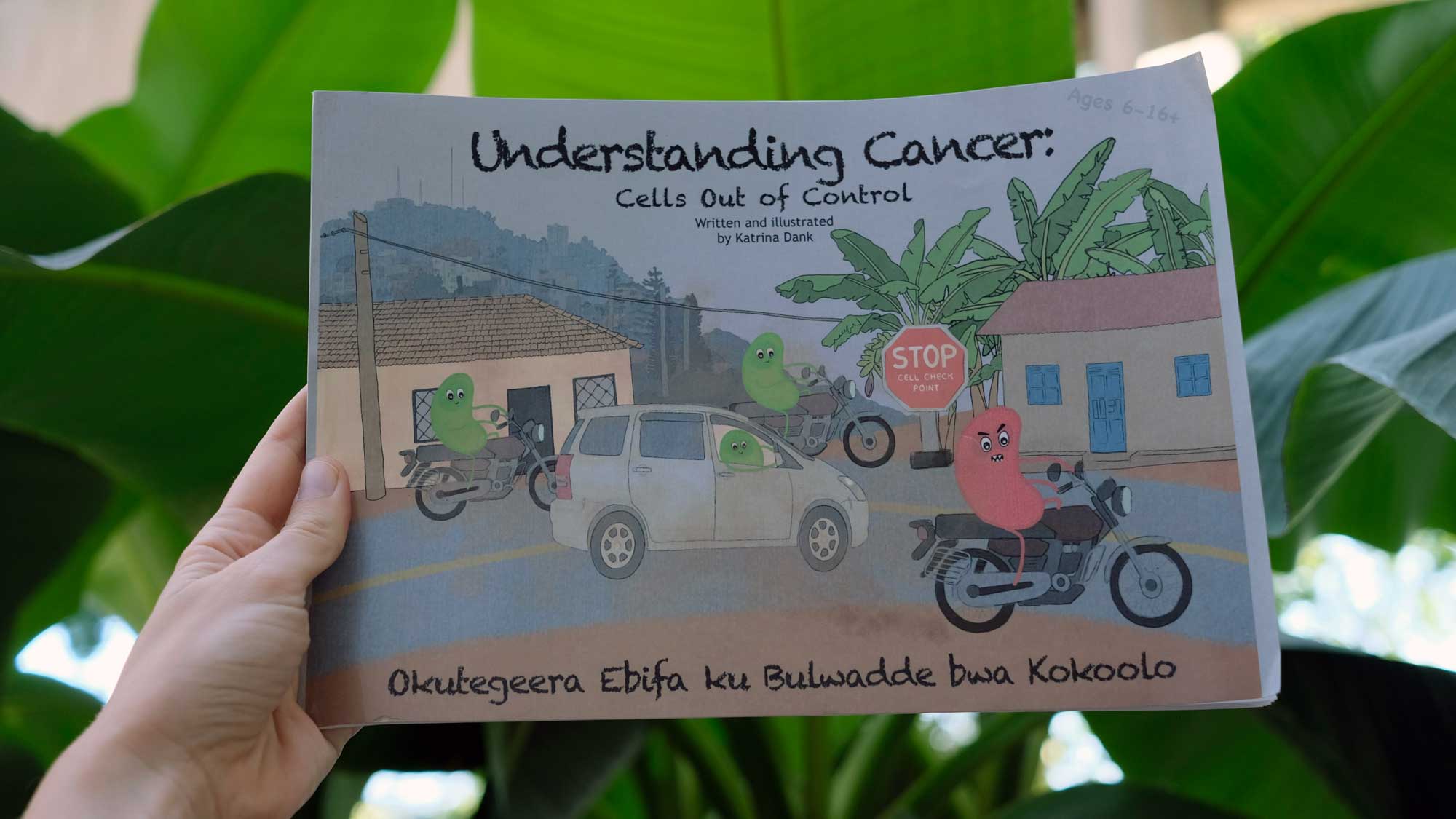

Project: Creating a picture book to increase cancer knowledge in Uganda Cancer Institute’s pediatric population.

Background: The Uganda Cancer Institute (UCI) is the only public cancer-specific treatment facility in Uganda, a country with one of the highest incidences of pediatric cancer in the world. UCI’s educational materials and outreach division use text-heavy materials catered to adult audiences. Additionally, providers at UCI experience a high patient burden, seeing 25 to 75 patients a day, limiting physician-facilitated patient education. Thus, UCI’s pediatric population receives no formal educational outreach.

My project sought to create an image-based educational tool that not only addresses this unreached audience, but also increases accessibility among the country’s 52 distinct languages and low literacy populations.

The project: I spent my first three weeks talking with physicians, patients and parents in the outpatient pediatric oncology clinic and comprehensive community cancer prevention department to identify key cancer-related issues. I used these experiences to inform the content of the 30-page picture book I proceeded to write.

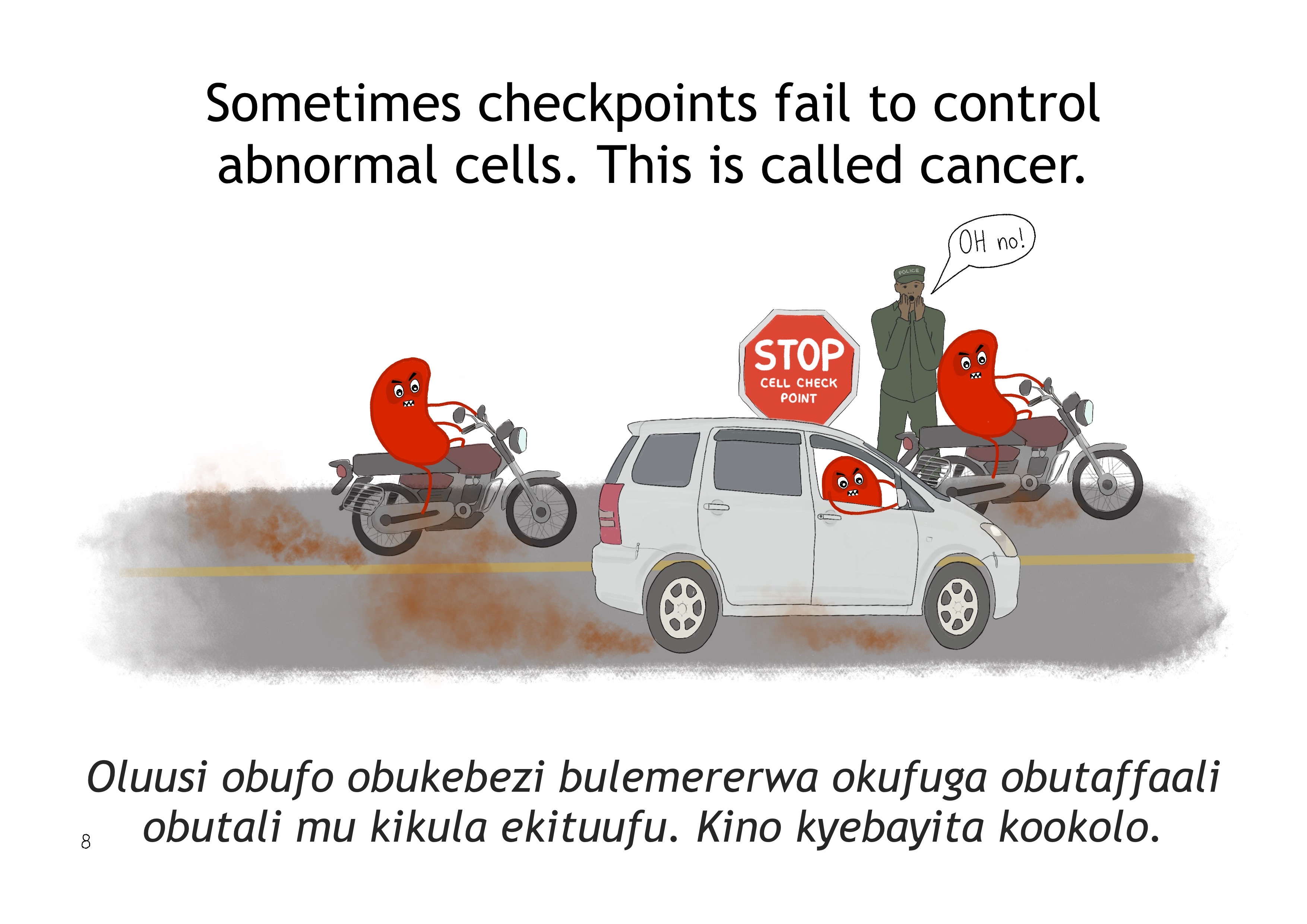

I created all the illustrations for the book, with careful attention for incorporating culturally relevant imagery. For example, the primary analogy for the mechanism of cancer was represented by angry-looking cells on motorbikes (“boda bodas”) disobeying police checkpoints which are a ubiquitous sight throughout the country.

I confirmed the target age range by working with a cohort of primary school students ages 7-10 who read the book aloud, noting unfamiliar words, and reflected on what they learned. Feedback from colleagues was facilitated by presenting a draft of the book to more than 40 UCI staff.

In addition to the text in English, the main language for healthcare in Uganda, a Luganda version of the text was included at the bottom of each page as it is the primary language in the Central Region of Uganda where UCI’s main campus resides.

Results: The final book achieved the following content goals:

- Provides a scientific, cell-level basis of understanding of cancer

- Reduces stigma and normalizes the patient experience

- Encourages early presentation to medical facilities

- Provides a rationale to reduce loss to follow-up care

- Educates the community on risk prevention strategies

- Reinforces learning through a self-directed quiz

- Rewards rereading materials by providing stickers for each time the book is read

The original intention of the book was solely as a resource for patients passing their time waiting to see physicians in the outpatient pediatric department. However, as word spread of my project, more departments and community organizations requested copies.

When I left, an initial round of 18 books were printed and distributed across five pediatric care settings. A poster version of the material was made for the comprehensive community cancer prevention team’s outreach. There are three hostels in Kampala with the capacity for 82 children and their caretakers to stay while receiving care away from home, and each of these facilities received a book.

Most notably, a partnership was established with the Uganda Child Cancer Foundation (UCCF) which has an existing Caring About Cancer club program in 238 secondary schools across Uganda. They had been looking to expand to primary schools, but lacked the necessary materials or curriculum. This book provided the missing piece, permitting involved secondary students to go to primary schools to conduct classroom readings – drastically expanding the reach of the book.

Reflections: I never could have imagined how much positive feedback I would receive from colleagues and community members when I set out to do this project. It was amazing how the freedom of an 8-week project with no explicit agenda had the potential to create such a mutually beneficial outcome.

I’ve always hoped to incorporate international work into my future medical career, but have struggled with how to do so in a sustainable and ethical way. This model of having no ulterior agenda/funding source, explicitly dedicating time to get to know the local context, and creating an educational material than can outlive my stay is something I can see inspiring future work even within limited time constraints.

Focusing education outreach on the pediatric population was another element of the project that surprised me with its potential for maximizing the effectiveness of my time. Children are enthusiastic learners, more willing to accept new ideas, and go on to teach their parents and community about what they learned. The role of children is especially relevant in Uganda as it is the second youngest country in the world.

When receiving feedback from the physician I worked with the most, Dr. Geriga, I learned about the historical significance of educating children on relevant health issues in Uganda.

In his final speech he said, “At first it was for children who are waiting to see doctors and children on wards, to have some literature for them. But now when I look at this book today I remember many years back when I was very young, the game changer in Uganda’s HIV journey was like this when I was in primary school. For those of you who weren’t there, the game changer for the HIV campaign in the early 90’s was just a booklet like this dropped in all the primary schools. And it communicated through pictures in the way this one is communicating. The NPCA’s strategy was delivered through this and it really made an impact. So now when I look at this my mind goes back 30 years. We need to take advantage of this beginning to change the face of cancer among children in Uganda.”

This was the first I had heard of this historical strategy, but even limited research into the NPCA’s historical efforts shows the greatest chunk of initial funding was dedicated to education campaigns and in this day and age, Uganda is one of the few countries in the world viewed to have a success story when it comes to reversing the bleak HIV statistics in the country. In fact, in the early days of my project when I was talking to community members “Cancer is the new HIV in Uganda” and similar sentiments were common among community members.

This gives me hope that my book may help be part of the new educational solution to reversing this healthcare reality.

Thank you’s:

Thank you to Nambalirwa Priscilla, Fadhil Geriga, Alfred Jotho, Mugisha Mugume Noleb, Derrick Bary Abila, Warren Phipps, and Andrea Towlerton for their advising and feedback throughout the process. The Luganda translations would not have been possible without the help of Jacob Malaga, Jacqueline Asea, Ruth Nakuya, and Constance Namirembe. Thank you to Olive Birungi, my daily lunch crew, desk neighbors, and everyone at UCI and ACCF who made me feel so welcome during my stay in Kampala. Lastly, thank you to Daniel Hill for all his support throughout the process including funding the initial round of printing.

What’s next: Since leaving Uganda, UCCF has connected me with Solterre, a nonprofit in the north focusing on pediatric cancer. They have offered to translate the book into Acholi and Swahili before distributing it within the region of their care. Working with colleagues, I was able to identify five additional languages for future translation of materials to most effectively capture the diverse language groups of Uganda. I am also looking into conducting an official IRB-approved study on the efficacy of the educational materials in improving cancer knowledge.

Meanwhile, I am in the process of launching a fundraiser to deliver 500+ additional copies of the book, hopefully in early December.